07 Feb 2024 - Margie Ruffin

Let’s say you have servers somewhere far away, potentially hosted by your company or some other provider, but you sometimes wonder if you could ever fully trust that no one is doing anything sketchy on them. You may ask yourself, how can I prove that my machines have not been tampered with, or how can I prove that they are being tampered with? You may wonder how you can trust them. With Remote Attestation, you don’t have to wonder; you can use existing hardware solutions to prove that the machines can be trusted and are indeed in a secure state.

This article is Part 1 of this blog series revolving around Remote Attestation and Keylime. In this piece, we will briefly examine the concept of Remote Attestation and several of its components. In the end, I will introduce you to a software solution called Keylime, which you can use to implement this type of attestation.

Cloud service providers, for example, inherently ask their customers to put significant trust in them each time they provide a service. Where does that trust come from? Why should a customer believe anything that a provider says is true? In reality, they shouldn’t unless it has been proven that their running systems have not been tampered with. Here is where Remote Attestation comes in. Attestation is designed to prove a property of a system to a third party, which, in this case, is you. It can provide proof that the execution environment can be trusted before beginning to execute code or before proceeding to deliver any secret information.

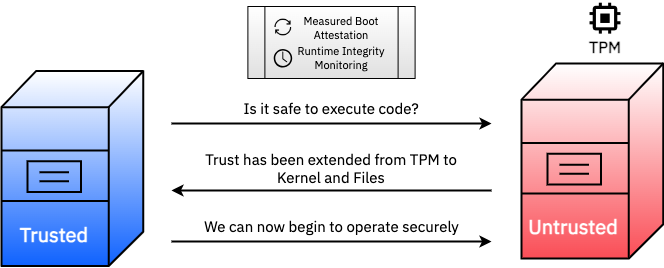

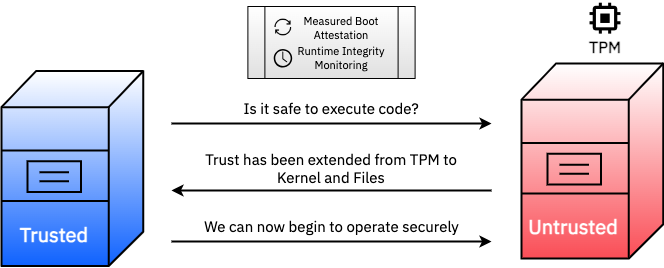

This framework allows changes to the user’s computer, the attested (your remote servers), to be detected by authorized parties, the attestors (you on your local servers). In this framework, the attestor machine is already trusted by the customers, while the nodes they are provisioning through the cloud service providers are not.

Remote attestation can provide different services, such as measured boot attestation and runtime integrity monitoring, using a hardware-based cryptographic “Root of Trust” (RoT), for example, a Trusted Platform Module (TPM). A TPM is a chip that conforms to the standards of a secure cryptoprocessor, which is a dedicated microcontroller designed to secure hardware through integrated cryptographic keys. It is used to store artifacts that work to authenticate the platform it is on. Recently, we have seen a shift towards firmware TPMs, which come with their own set of pros and cons.

Figure 1: Remote Attestation provides trust between an untrusted party and a trusted party. You can use services like Measured Boot Attestation and Runtime Integrity Monitoring to prove systems are trustworthy.

In this article, we will detail the different aspects of remote attestation based on the following sections:

Unified Extended Firmware Interface (UEFI) Secure Boot is a security measure developed to ensure that a device is booted using only software trusted by the Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM). The goal is to prevent malicious software from being loaded and executed early in the boot process. During secure boot, the next component is verified by the component before.

Secure Boot prevents boot if the signature cannot be validated against a certificate enrolled in the bootchain. For example, if someone changes the kernel to a custom one, it is not signed by the OS vendor. This causes the boot to stop because the bootloader couldn’t verify the signature. The process of checking the kernel’s signatures occurs before the OS ever runs.

Measured boot technologies rely on a RoT, a source that can always be trusted within a cryptographic system. The RoT is a component that performs one or more security-specific functions, such as measurement, storage, reporting, verification, and/or update. It is trusted always to behave in the expected manner, because its misbehavior cannot be detected (such as by measurement) under normal operation. The RoT cannot be modified at all or cannot be modified without cryptographic credentials.

Unlike Secure Boot, Measured Boot will measure each startup component, including firmware, all the way up to the boot drivers. A hash is taken at the first step in the boot process and is extended for the next object(s) in the chain. It is stored in a chosen Platform Configuration Register (PCR), which is a memory location in the TPM. The extend operation allows for data to be appended to the value already stored in the PCR. A hash of the newly formed data is the result, and that is stored back into the PCR. The final hash can be seen as a checksum of log events. With this, an auditor can later come and validate the logs by computing the expected PCR values from the log and then comparing them to the PCR values of the TPM. One can verify the validity of the kernel because measured boot checks each component in the start-up process, and the final hash value encapsulates all of them in their present (at that time) state. With Measured Boot, the boot process is never stopped, but it provides the necessary information to detect attacks.

These two processes go hand-in-hand to ensure a trusted Operating System (O/S) boots. Measured Boot assesses the system from the processor powering on to the point where the operating system is ready to run. The issue is that once the O/S is booted, Measured Boot stops, and its output is encapsulated into the measured boot log and the PCR values in the TPM. Now that the O/S is unguarded, it is conceivable that someone could manage to navigate to the boot event log, the PCRs, and the TPM and alter them retroactively. They could even go as far as to replace the TPM device with a virtual TPM. However, even if someone did manage to switch out the TPM to alter the boot event log, with the unique Endorsement Key (EK) bound to the TPM and its EK certificate signed by a trusted certificate authority, the identity of a TPM can be verified before trust is established.

Secure Boot works to guard the UEFI by enforcing integrity locally using digital signatures. Measured Boot will check the component and take a hash of it to be stored for later to help prove whether or not it has been tampered with. The UEFI will prevent an unsigned kernel from booting properly if the hashes taken do not match at the time and will boot the kernel in “lockdown mode,” which will prevent alterations to it. Measured boot will allow for integrity checking after the system is booted.

Measured Boot allows us to verify the configuration of Secure Boot after it has taken place. Secure boot guards the post-boot integrity of the kernel, i.e., making sure that only trusted software is booted, by keeping it in “lockdown mode” in case something suspicious happens. Both are needed to get to a point where we have a completely booted system with a kernel that can be trusted.

In any production environment, many different types of nodes can be found. One can use remote attestation in combination with measured boot to determine and verifiy a platform’s configuration. A measured boot reference state can be specified ahead of time for each node type and given to the remote attestation operator, along with a measured boot policy that is used to instruct the verifier on how to do the comparison. With this mechanism in place, the operator can ensure the validity of the kernels for their entire cluster.

The two previously described aspects of Remote Attestation are helpful for a one-time check to see if the server you have provisioned was altered before it was booted and running. But what can you do if you want to continuously make sure that things aren’t being altered in real time? You can use Linux kernel’s Integrity Measurement Architecture (IMA) for that. Implementing IMA with your Remote Attestation framework lets you detect if files have been accidentally or maliciously altered. With Secure and Measured Boot enabled, we established a chain of trust from the TPM, which also serves as IMA’s RoT, all the way up to the running kernel. Because the kernel is now trusted, we can trust it to measure files with IMA, thus extending that trust to the files.

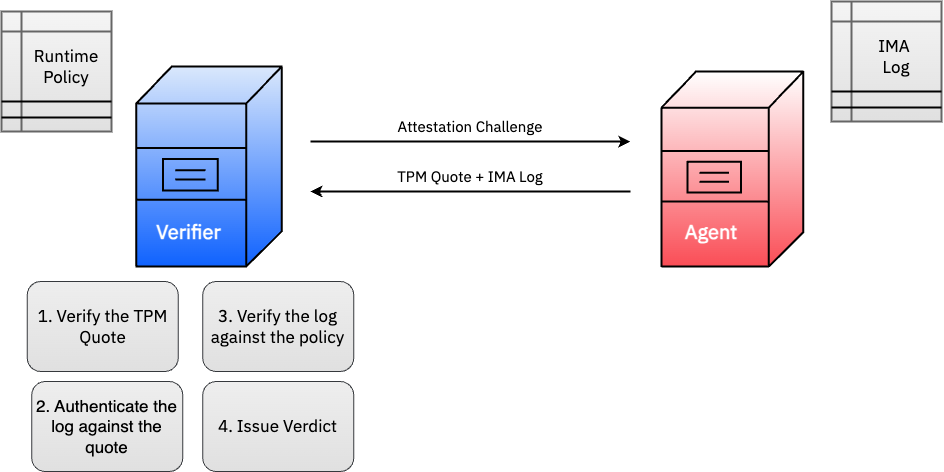

In just a few short steps, we can see how IMA works.

Figure 2: We show the steps it takes to issue a verdict for a running system’s trustworthiness using Integrity Measurement Architecture (IMA).

IMA also has another capability worth mentioning. Instead of using a third party to appraise files as described above, IMA has the ability to do its own local appraisals. IMA collects file hashes and places them in kernel memory where other applications cannot access or modify them. If it were configured to do so, if a file with an IMA hash is opened for reading or executing, the appraisal extension will check to see if the contents match the stored hash. This extension forbids any operation over a specific file in case the current measurement does not match the previous one unless stated otherwise. The stored hash is the value previously stored in the measurement file within the kernel memory for that file. The ima_appraise kernel command-line parameter will determine what happens if they don’t match. If it is set to “enforce,” access to the file is denied, while “fix” will update the IMA xattr with the new value.

Now that you know a little about some of the important components of Remote Attestation, I would like to introduce you to Keylime, a highly scalable, TPM-based remote boot attestation and runtime integrity measurement solution. Keylime helps to provide trust between its users and remote nodes.

Using a hardware-based cryptographic RoT, a Keylime user can monitor their remote nodes for system tampering at boot while continuously in service. Keylime is an alert system that will notify the operator by raising a flag if measured boot attestation fails (i.e., someone has altered the kernel) or if runtime integrity monitoring fails (i.e., someone maliciously altered an executable system file). Using a hardware-based cryptographic RoT, a Keylime user can monitor their remote nodes for system tampering at boot while continuously in service. Keylime is an alert system that will notify the operator by raising a flag if measured boot attestation fails (i.e., someone has altered the kernel) or if runtime integrity monitoring fails (i.e., someone maliciously altered an executable system file).

The Keylime tool mainly consists of 4 components: an agent, a verifier, a registrar, and a commandline tool called the tenant.

The agent is a service that runs on an untrusted operating system, which is to be attested. It communicates with the TPM and collects necessary data to make attestation possible.

The verifier is in charge of implementing the attestation of the agent. Essentially, it is the component saying yes, the agent trusted, or no, the agent is not trusted. If the agent fails attestation, the verifier can also send a revocation message (i.e., raise a flag) to alert the Keylime operator of a failed state.

The registrar manages the agent enrollment process. Once the agent is enrolled in the registrar, it is ready for attestation.

And lastly, the tenant is a commandline management tool by Keylime used to manage the agents. It can do various tasks, including adding or removing the agent from attestation and checking its status. If you want to read in further detail about each of the components of Keylime, see the documentation here.

As you’ve just read, measured boot ensures that a machine has not been tampered with before it begins running any processes. Keylime makes use of recently updated kernel modules, tpm2_tools (5.0 or later), secure boot, and a “recent enough” version of grub (2.06 or later) to provide a scalable measured boot solution to clusters that could potentially have a large number of different types of nodes in a very flexible manner.

Through Keylime, the Tenant specifies a “measured boot reference state” or mb_refstate. The Keylime Verifier uses this reference state to compare to the boot log gathered by the Keylime Agent from the kernel.

There is another optional feature that Keylime can use for performing measured boot attestation. A “measured boot policy” or mb_policy is the information used to instruct the Keylime Verifier how to compare the mb_refstate and the boot log. The default settings are “accept all,” but can be modified to suit an individual’s needs.

For measured boot attestation to be fully useful, Keylime operators should provide their own measured boot reference state and measured boot policy. Ideally, you want to create a policy that is both meaningful and generic enough to be applied to a set of nodes. One can change the pre-provided mb_policy to suit their needs rather than attempting to write a brand new one from scratch.

If you want to read more about how to enable measured boot on Keylime, you can do that here.

To use Keylime’s Runtime Integrity Monitoring, there are a few steps that you will need to take to either enable Linux IMA or ensure that it is already running. As we learned a few sections ago, IMA is used to measure the contents of files at runtime. However, before it can do that, you must tell it what to measure using an ima-policy. In the Keylime repository, you will find an example policy that can be used, and in the documentation, you will find instructions on enabling IMA.

In Keylime, a runtime policy is a list of “golden” cryptographic hashes of files in their untampered state used for IMA verification. The Keylime verifier will load the runtime policy and use it to validate the agent’s file states that are loaded onto the TPM. If the files have been tampered with, the hashes will not match, and Keylime will place the agent into a failed state. The Keylime agent and operating system itself are not deemed trustworthy by default. Given the setup only after the successful initial attestation, the system is deemed trustworthy, but it still can leave the trusted state at any moment and is, therefore, continuously attested. It is important to mention that Keylime also supports the verification of IMA file signatures, which also helps to detect modifications on immutable files and can be used to complement or even replace the allowlist of hashes in the runtime policy if all relevant executables and libraries are signed. However, this setup is beyond the scope of this introduction.

If you want to read more about how to build a runtime policy for Keylime and then deploy it, you can do that here.

Remote attestation is a way to create peace of mind that you can and will detect when something is amiss inside a cluster. By building a chain of trust from hardware to software, you can ensure your data is protected.

Keylime is commonly used either on bare metal hardware or in VMs where the TPM is emulated but, from the VM side, treated the same as a hardware TPM. In this article, we have seen what Keylime can detect:

In Keylime, you can implement whatever you want around the revocation hook that is provided, e.g., remove the node from the cluster when it detects that it is compromised. This makes Keylime a great tool to have for someone managing a lot of machines!

Want to get in on all the action? Check out blog post part 2 (coming soon) in this series, This is Keylime, a BEAST, but Totally Worth It, for a step-by-step tutorial on how to set up Keylime on your own machines.